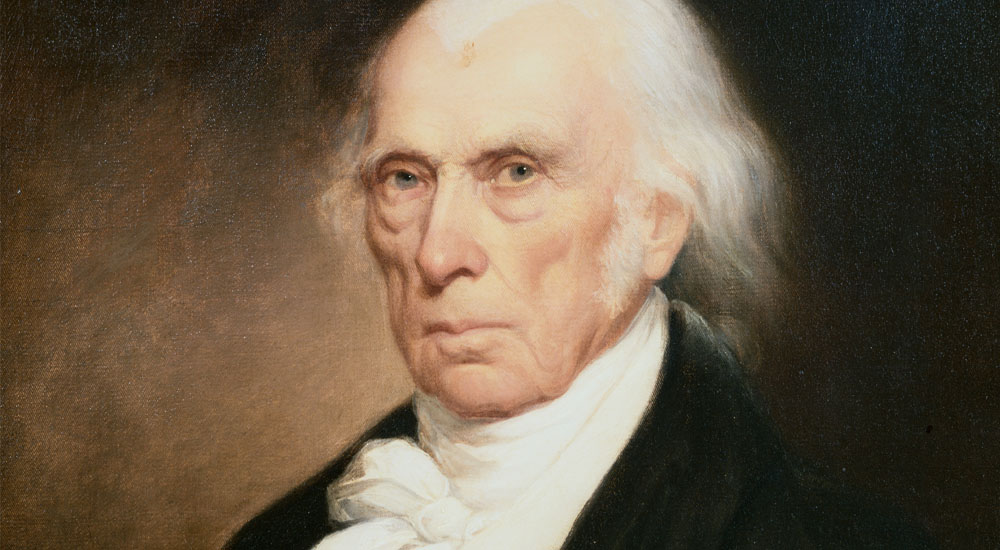

It took just two multi-million dollar donations to Monticello and Montpelier and the insistence of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, but the effort to redefine Thomas Jefferson and James Madison as contemptible hypocrites is on in a big way.

Two articles from the New York Post are bringing to light several changes at both Monticello and Montpelier, and visitors to the national landmarks are rather unimpressed:

“A one hour Critical Race Theory experience disguised as a tour,” groused Mike Lapolla of Tulsa, Okla., after visiting last August.

“They really miss the mark,” Greg Hancock of Mesa, Ariz. posted last week. “We left disappointed not having learned more about … the creation of the Constitution.”

“The worst part were the gross historical inaccuracies and constant bias exhibited by the tour guide,” complained AlexZ, who visited July 8.

“It’s been inspirational … I guess,” shrugged John from Wisconsin after taking the $35 guided tour.

One visitor to Monticello compared it to a “besmirchment derby” where any mention of Jefferson’s name seemed required to come with a denigration.

David M. Rubenstein, a philanthropist who earned his fortune after a stint as CEO of Carlyle Group, donated $20 million to Monticello in 2015 after a $10 million donation to Montpelier in 2014 — all with the stated effort of revising the experience at both locations to enhancing the stories of both Jefferson and Madison to include the experience of African slavery:

Critics observe that while it is one thing to complement the story of Jefferson and Madison with the stories of those who, in Jefferson’s euphemism, labor for their happiness, the pendulum has swung so wildly as to obscure what made Jefferson and Madison unique for their times — and why we celebrate both men even today.

For instance, if the Rubenstein Foundation had purchased any notable Virginia plantation home (and there are many) and researched the history of the enslaved populations there, built exhibits and museums, and financed such an operation on the scale of Monticello and Montpelier, precisely how many people would come to visit such a museum.

We already know the answer to that question. There’s a good reason why we know the answer. Because the difference is that unlike their peers, both Jefferson and Madison looked to the horizon to a better day.

Perfectly? Not in the slightest… yet stack their shared virtues: the Declaration of Independence, the US Constitution, the Statute for Religious Freedom, the Virginia and Kentucky Resolves, four terms as president of the United States and founders of the University of Virginia.

Should they have been as irresolute as their neighbors because their efforts would be spat upon by 21st century progressives who never question the price of their clothing, the cheap cost of energy, and all that is spent preserving the Pax Americana? What might their grandchildren think of a society that speaks tolerance and inclusion but really means the justification of violence in the hopes the arc of history bends towards justice?

Facts are, most Americans have no tolerance for the imposition of propaganda in the effort to overcorrect the whitewashing of American history. The long history of humanity is — to borrow from Thomas Hobbes — nasty, brutish, and short. Human suffering is by no means unique, although each person does uniquely suffer.

Yet in both Jefferson and Madison there is much to preserve. Neither were perfect, and in many cases Jefferson’s own views towards those of African descent coupled with Madison’s Potemkin village at Montpelier in an attempt to show African slavery as a benign and gentle concept were reprehensible representations that any historian should look to place into its rightful context. Yet this tapestry of human suffering was the norm in Virginia and elsewhere. What we celebrate and remember in Jefferson and Madison is the exceptional, or rather the hope for the exceptional that one day we might fulfill what the Declaration of Independence asserts are our inalienable rights — not in a perfect Utopia but a more perfect Union of balanced factions and constitutional process.

Did we mention that attendance at most historical sites is down? Not for lack of history, mind you, but for lack of interest. Transforming sites such as Monticello and Montpelier into Soviet-style propaganda outfits drives historians who know better away — and certainly doesn’t foster any love for history as a profession writ large.

Americans honor Jefferson and Madison not for their flaws but in spite of them. Those who are stewards of the national treasures might do well to refrain from prostituting them in the name of ideological sentiment if we truly are seeking to honor Jefferson and Madison as men and not marble.