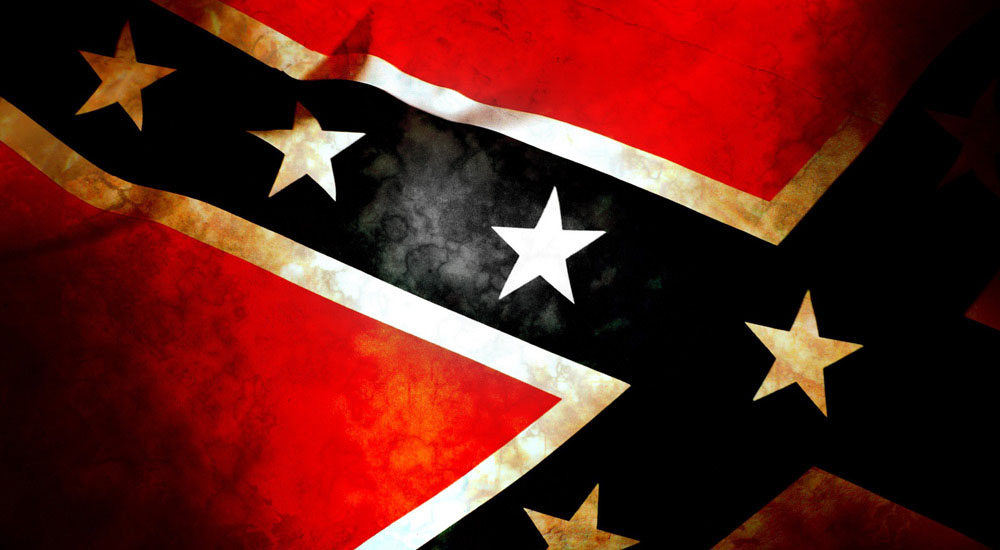

When the Albemarle County School Board met this week to discuss the division’s dress policy, like many things in Charlottesville area, it ended like many expected – in chaos. The school division has caught some flak from the Hate-Free School Coalition, which has criticized the board for not “explicitly banning Confederate images,” in an age when the symbol consumes conversations in the area.

When Board Chairwoman Kate Acuff began to speak about the dress policy, a cacophony of lambasters could be heard outside in the meeting chamber’s lobby. Suddenly, approximately 50 community members filled rows of folding chairs, some wearing teal-colored shirts donning the phrase: “Ban it now.”

Lara Harrison, a member leading the Hate-Free Schools Coalition, said the group was there to hold a “people’s meeting,” according to a report from the Daily Progress. When the group entered the board meeting, Harrison “gave a speech,” in which she reiterated demands to ban Confederate imagery and charged that the Albemarle County School Board has refused to work with community members.

Harrison also called Acuff’s reiteration of public comment rules a “threat of violence against community members,” and demanded that Acuff and board member Jason Buyaki resign, explaining that Buyaki had worn a Confederate flag-laden tie at last week’s meeting.

“We are not going anywhere, and the more they try to silence us, the louder we will be,” Harrison proclaimed, followed by a background of cheering.

Reportedly, Buyaki said he wore the tie as a “historical lesson” about “various flags flown over the U.S.,” not as a statement on the division’s dress code proposal.

The Central Virginia school district says that banning Confederate symbols would open it up to legal liability for violating students’ First Amendment rights.

Supreme Court jurisprudence has been made on this notion before, nearly 50 years ago.

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court ruled on a situation surrounding students wearing armbands during the day at a public school to protest the Vietnam War. The school had created a policy that stated that any student wearing an armband would be asked to remove it, with refusal to do so resulting in suspension from school. Beth Tinker and Christopher Eckhardt, two high school students involved in the situation, wore their armbands to school and were sent home when the administration enforced the policy.

In a 7-2 majority, the Supreme Court held that armbands represented “pure speech” that is entirely separate from the actions or conduct of those participating in it. Furthermore, the Court held that the students did not lose their First Amendment rights to freedom of speech when they stepped onto school property.

For school administrators to justify interfering in such speech, they would have to prove that the conduct in question would “materially and substantially interfere” with the operation of the school, with actual interference in school activity occurring, not merely the fear of possible disruption.

Also, it is important to note that this decision was handed down by a Supreme Court with a 6-3 liberal-conservative split, with four liberal joining the conservatives to ensure freedom of expression.

Nevertheless, to actually ban Confederate imagery from the school division, administrators must prove that such imagery causes actual disruption. Based on Supreme Court precedent, an actual disruption may have to occur before anything can be done.

During the board meeting, another speaker attempted to start a chant, but was promptly stopped by the law enforcement officers that showed up. After the speaker refused to quiet down and refused a request to disperse, she was escorted out by police.

As others joined in the disruption, six people in all were arrested. According to the report, one man allegedly kicked an officer and was pushed to the ground, where the struggle continued.

Following the meeting, division spokesman Phil Giaramita said the “School Board’s focus tonight was on meeting its constitutional and legal responsibilities. Tonight’s protest was a concern only to the extent that it could have once again disrupted the ability of the School Board to complete the business of the school division. That did not happen.”

Albemarle Commonwealth’s Attorney Robert Tracci also responded to the protest.

“While I will not speak to pending criminal cases, the right of free expression provides no right to engage in criminal misconduct,” he said. “Those who violate the law under any pretext within the jurisdiction of the County of Albemarle will be appropriately prosecuted by the office I am privileged to serve.”

A productive conversation could have been held with those that wish to ban Confederate imagery in schools, but that hasn’t happened yet.