In California, Senate Bill 219 was signed into law recently by Governor Jerry Brown, which law makes it “unlawful” for long-term care facilities to “willfully and repeatedly fail to use a resident’s preferred name or pronouns after being clearly informed of the preferred name or pronouns.”

To be sure, this law only (currently) applies to long-term care facilities, but it seems clear that this is a legislative trial balloon, so to speak, the implications of which can more broadly be applied to California’s constitutional civil rights.

Imagine a state (in other words) in which one is compelled to use an individual’s “preferred pronouns” in all civil transactions. Such a state was debated last year when Canada passed C-16, an amendment to its Human Rights Acts, which added the terms “gender identity or expression” to its protected classes. (These debates were made somewhat famous by University of Toronto professor Dr. Jordan Peterson.) But unlike the California legislation, the Canadian law did not explicitly compel the use of pronouns (some believe it does implicitly). The word “pronoun” is not even found in the legislation passed by our Northern friends.

For those working in long-term care facilities in California, they are now compelled to ascertain and memorize complete pronoun declensions for individuals based entirely on preference. How ridiculous can this get?

In New York City, there are 31 recognized gender distinctions – which is to say, theoretically, that each can have its own pronoun declension. I should clarify: that currently we are only considering each theoretical 3rd person singular pronoun (more on that later).

Historically, we have consolidated pronouns in our language, not expanded them. In 20th-century English, there were 7 distinct gender expressions in our 3rd person singular pronouns in classical declension: he, she, it, his, her, its, him. (I am conveniently considering the pronoun “hers” a subset of the genitive case, much like the partitive genitive case in the declension of common nouns.)

In Old English, however, there were a total of 10 distinct gender 3rd-person singular gender expressions: He, Heo, Hit, His (m.), Hire, His (n.), Him (m.), Him (n.), Hine, and Hie. This is a reduction from classical Latin’s 3rd-person singular declension of 14 distinct gender expressions. In other words, the use of 3rd-person singular pronouns has been reduced by half over the past millennium.

But if we accept New York City’s list of accepted gender identities – even if we generously make the dative, accusative, and ablative cases all the same expression (as we did in the 20th Century) – we suddenly have a grand total of 91 possible distinct gender expressions we must incorporate into our language. (The table below is a theoretical example only. The different genders are those accepted by New York City, but the declensions are purely conjectural. It does illustrate, however, the potential grammatical absurdity. NB: I had to switch the rows and columns of the case/gender for the sake of readability.)

Rather than gravitating linguistically toward a more universal use of 3rd-person singular pronouns – as we have for centuries – this represents an explosion in the multiplicity of classifications and distinctions among our single human race.

But notice, we have only been concerned with the declension of 3rd-person singular pronouns. Why stop there? California’s law (and New York City’s legal guidance) makes no distinction of the classification of an individual’s “preferred pronouns.” They only refer to “pronouns” generically, which in California’s case (because it is a legal statute), can be interpreted to extend beyond the 3rd-person singular pronouns toward 2nd-person pronouns, relative pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, distributive pronouns, and others.

Twentieth-century English did not distinguish gender in its demonstrative pronouns (this, that, these those), but it used to. Latin does distinguish among masculine, feminine, and neuter demonstrative pronouns (ille, illa, illud), and Spanish still distinguishes between the masculine and feminine demonstrative pronouns (èste, èsta).

There are even languages in existence today which still distinguish between genders in the 2nd-person singular expression (you, your). The Korana language in South Africa, for example, distinguishes the masculine “you” (sa-s) from the feminine “you” (sa-ts) in its singular 2nd-person expression. There is no real reason why English cannot adopt that system to avoid offending those who do not identify as a “you.”

Imagine now the complexity of scuttling the binary/trinary grammatical system and adopting New York City’s tricenarious pronoun expression. Now the table looks like this (you’ll have to click to read the whole thing):

That’s nearly 500 NEW distinct pronouns of gender expression added to the lexicon, just like that. And this is just a sample of the pronouns that could be affected. I did not include intensive pronouns (she herself), reciprocal pronouns (each other), negative pronouns (nobody, neither), and others. Remember, California’s law and the current social conversation do NOT constrain the impact only to 3rd-person singular pronouns. Also remember that the law and conversation are predicated strictly on subjective preference.

So there is no logical reason the conversation about pronouns can’t be extended to allow for the type of absurdity we see above. To be sure, there is no logical reason that the conversation can’t be extended to include MORE genders, or even more expressions of identity that have nothing to do with gender.

For example, I could take offense to the generalization of the second-person pronoun because it does not distinguish between singular and plural, and to call me “you” might imply that I am necessarily part of a collective. In that case, I would revert you, and compel you, to use Early Modern (or Jacobean) English in which the second person singular and plural are indeed distinct. One may no longer call me

“you,” but must call me “thou.” One may not call my properties “your,” but rather must describe them as “thy” or “thine”. It is, after all, my preference.

For that matter this author may take offense at being pressured to use the first-person pronouns “I, me, my” because of those words’ individualistic connotations that reject collectivism and social plurality. In that case, this author would by preference insist that the use of “We, Us, Our” be acceptable in the singular sense, or even that the use of Our identifying label be the proper first-person pronoun. This is the preference of Tenebras Lux, and Tenebras Lux will not tolerate those who do not accept Tenebras Lux’s preference of pronouns.

While the declension tables and the hypothetical examples above do demonstrate a certain grammatical and linguistic absurdity, it is only an argument of impracticability. It’s not a transcendent philosophical argument; it’s an argument from pragmatism. In other words, it may be impractical to allow for the expansion of new pronouns based on the evidence above, but it’s not impossible or contradictory to do so (again, based on the evidence above).

So we may have to memorize 500 new pronouns (or more), but if that’s the price we pay to demonstrate a tolerance and support for others’ identities, so be it. It can’t be that much harder than memorizing the Latin declension tables.

Right?

Wrong.

There is a transcendent philosophical case to be made against the incorporation of new pronouns besides the evident historical trend of pronoun consolidation instead of expansion. It has to do with the definition of “pronoun” itself.

A pronoun – contrary to the popular conversation being held today – is NOT an expression of identity. One might argue that a first-person singular pronoun (I, me, my) could be an expression of identity, but as we saw above it’s nothing more than a shortcut to reference distinct identity.

A pronoun, by definition, is a word in the place of (“pro-“) a noun. In personal pronouns, they are in the place of proper nouns, which are nouns of identity. Nouns of identity individualize, distinguish, separate; they emphasize unique qualities, essence and substance. They are names given to individuals, places, ships, or even product brands. A pronoun is not a noun of identity, but rather a noun of classification; it puts one word in the place of a noun of identity as a shortcut, so we are not forced to use Proper Nouns in every single case.

As an example, consider the sentence:

“See, how she leans her cheek upon her hand! O, that I were a glove upon that hand, that I might touch that cheek!”

Removing the pronouns that categorize similar (but not identical) identities, and including ONLY nouns of identity, makes the sentence read thus:

“See, how Juliet leans Juliet’s cheek upon Juliet’s hand! O, that Romeo were a glove upon the hand of Juliet, that Romeo might touch the cheek of Juliet.”

The pronouns in this case serve to categorize or classify Juliet and Romeo and their properties. They do not serve to identify Juliet and Romeo, in the sense that the pronouns themselves speak to no distinguishing or unique essence of either lover. They are simply nouns of classification in the place of nouns of identity.

This principle also applies not just to Proper Nouns, but to common nouns as well. Pronouns serve to categorize common nouns further than they already are into a simpler form.

Consider the paragraph above:

“So we may have to memorize 500 new pronouns (or more), but if that’s the price we pay to demonstrate a tolerance and support for others’ identities, so be it. It can’t be that much harder than memorizing the Latin declension tables.”

Without the use of pronouns to classify or categorize similar (but not identical) groups of common nouns, the paragraph must read:

“So, the individual readers of the article “How Ridiculous Can the Pronoun Argument Get?”, to include the author Tenebras Lux, may have to memorize 500 new pronouns (or a greater number than 500), but if memorizing 500 new pronouns (or a greater number than 500) is the price the individual readers of the article “How Ridiculous Can the Pronoun Argument Get?”, to include the author Tenebras Lux, must pay to demonstrate a tolerance and support for the identities of individuals among the totality of the human race, so be the price of memorizing 500 new pronouns (or a greater number than 500). Memorizing 500 new pronouns (or a greater number than 500) can’t be harder to a degree of small increments than memorizing the Latin declension tables.

You see (if I may call the reader “you”), pronouns are nothing more than common nouns that emphasize similarities rather than that which makes something unique, in the same way that we can use the word children (a common noun) as a substitute for John, Mary, and Peter (Proper Nouns of identity).

Anthropologists believe that common nouns – to include pronouns – have played a very important part in the development of civilization. Mario Livio, the great astrophysicist and mathematician, implies that the development of common nouns (the distinction between a single thing and things with similarities) was crucial to the development of mathematics, civilization, and knowledge itself.

Consider that every tree has at least one unique property about it that makes it separable from every other tree. In a world without common nouns, every tree would be named – or identified – individually in the same way that we name (or assign identity to) our children. But by recognizing that there are similarities among identities, we can categorize and classify them to help make sense of an objective reality.

Pronouns serve such a purpose. They remove the need to name every unique being according to its distinguishing subjective properties and allow for the grouping of such beings in accordance with their objective similarities. Perhaps this is one reason linguistic history has tended to reduce the number of pronouns rather than increase them.

The proponents of “a pronoun for every preference” are doing the opposite of what a pronoun is historically meant to do. Instead of using pronouns to remove (or bypass) distinct or identifying features, they are using pronouns to advance and amplify them. And what’s worse is that these amplifications are not done objectively, but rather they are done subjectively – by personal preference. This is a philosophical crisis. It is a direct consequence of existential thought.

Existentialism is by its own admission allergic to systematic approaches, or philosophical approaches that attempt cohere one part of existence with another part. Existentialism admits to a sort of chaos. “[The human situation] is a situation that cannot be reasoned about or captured in an abstract system,” writes modern existentialist Kevin Aho, “it can only be felt and made meaningful by the concrete choices and actions of the existing individual.”

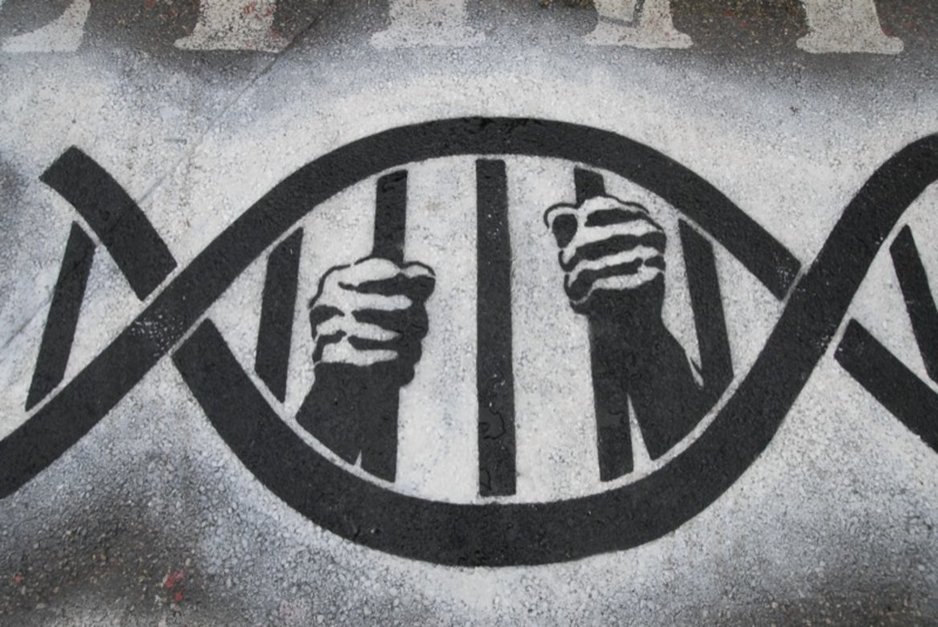

This means that subjectivity – personal preference – is in all cases superior to the attempt to categorize and classify objective similarities. This is how they argue that pronouns are an expression of subjective identity rather than objective classification. We don’t get to pick our pronouns based on subjective preference; they have evolved linguistically on the empirical and objective observations that distinguish one category of being from another. We do this by distinguishing between what is masculine and what is feminine. There are empirical ways to determine masculinity and femininity objectively – more so now than ever with the advent of genetic science. But to do so is anathema to the existentialist and the gender expansionists, because doing so necessarily systematizes gender; creating and bowing to a taxonomy based on beings apart from their “authentic self;” conforming to a social system that prioritizes the convenience of categories over the imbroglio of individuation. Such systems must be destroyed, and the authentic self must exercise its due freedom in its expression at all levels. That is the creed of existentialism.

Of course, the logical consequences of this anti-system is to return language and expression to complete subjectivity, removing common nouns, removing the distinction between the one and the many, removing all similarities from consideration and focusing only on what makes each individual different, unique, or “identifying.”

This is not a hard mental leap to make. It is already happening in academic circles and is filtering slowly into popular cultural expressions, such as the arts, as well as the psychiatric profession. Who hasn’t heard the expression, “Who cares what everyone else thinks?” as if to imply our expressions are completely subjective and individuated, and to emphasize non-conformity to social norms as a virtue? But that question, taken as a mantra, has philosophical consequences that go far beyond pronouns, far beyond issues of gender expression, and into the physical and mental well-being of humanity.