As the smoke of World War II cleared, Europeans and Americans were left with a vividly gory portrait of the capabilities of mankind and the consequences of ideas. Philosophy, religion, and science had left tens of millions bloodied, burned, and buried. Positivism was dead – man may advance in knowledge and technique, but he would never improve his purpose. Hypotheses of social morality, under the control and of care of a political rheostat, were tested in the global laboratory – and the tests exploded.

And yet peace was still not an option.

Dread and anxiety became more palpable as the threat of nuclear annihilation engulfed the world in a very real sense.

“Is God Dead?” TIME Magazine asked its readers in 1966, and pointed to the “existential anguish” such a question might provoke. Simone de Beauvoir articulated amidst her own angst, “It was easier for me to think of a world without a creator than of a creator loaded with all the contradictions of the world.”[1]

Everything – especially existence – seemed to be absurd and meaningless to an increasingly secularized world.

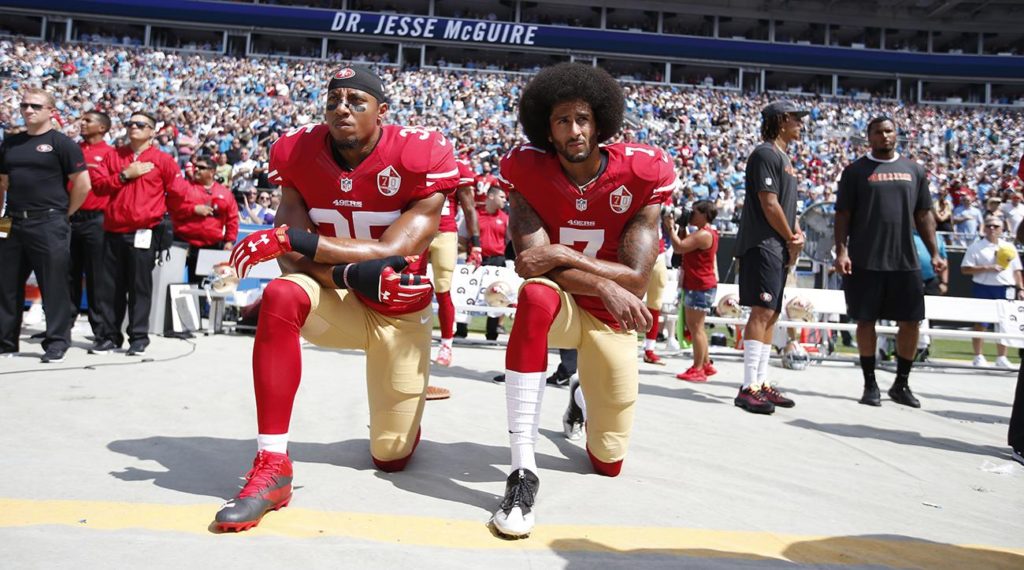

What does this have to do with Nike? They are celebrating the 30th anniversary of their “Just Do It” campaign – controversially, by choosing Colin Kaepernick as the face of its campaign. But Kaepernick is not the problem with the campaign – I believe the controversy surrounding him is only a symptom. The problem is with the slogan itself – and its subsurface themes that elevate authenticity over truth, liberty over morality, existence over essence.

Nike’s slogan, coined in 1988, is a pithy expression of the crisis of theoretical and practical thought that faced late 20th-century western civilization. If life is absurd and meaningless, how shall we then live? Shall we then live?

Albert Camus asked his readers to contemplate seriously the theoretical and practical consequences of suicide. “There is but one serious philosophical problem,” he opens, “and that is suicide.” Suicide, Camus acknowledged, is a logical consequence of an awareness of the absurd. One accepts, by living, absurdity and meaninglessness “cannot be settled,” but suicide is “acceptance at its extreme.”

But Camus could not bring himself to promote existential extermination, despite his acute awareness of the perpetual despair one purchased with the currency of continued life. “Living is keeping the absurd alive.” Nevertheless, Camus insists, despite one’s absurd existence and dreadful future, “by the mere activity of consciousness I transform into a rule of life what was an invitation to death… The preceding merely defines a way of thinking. The point is to live.”

For Camus, “to live without appeal,” was to reject mystical “leaps” of faith, as well as to reject suicide, but rather to embrace living within the absurd “solely with what he knows, to accommodate himself to what is,” that is, to live freely with the certainty that nothing is certain, except perhaps his own desires.

Paul Tillich, a Lutheran existentialist, recognized in 1952 that this age was best described as an “age of anxiety”—anxiety being that state in which “a being is aware of its nonbeing.” Certainly an intense awareness in the aftermath of World War II and the Cold War. However, says Tillich, “the courage to take the anxiety of meaninglessness upon oneself is the boundary line up to which the courage to be can go… The Courage to Be is the God who appears when God has disappeared in the anxiety of doubt.”

To Tillich, man was “finite freedom,” which freedom determined man’s ability “to determine himself through decisions in the center of his being,” but he always had as a responsibility to his being, “to be.”

For Jean Paul Sartre, the freedom of existence required not just the responsibility “to be,” but the responsibility “to do.” In order to even approach pure being – which always eludes the existentialist – one must first “do.” “Desire,” Sartre tells us, “is a lack of being.” Therefore, in order to satisfy this lack, one must have what one lacks; in order to have what one lacks, one must do. By doing and therefore having, one is then being: “to do, to have, to be.”

This is the paradigm in which Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign emerged – and it is my contention it is STILL the paradigm under which the campaign operates, and under which we receive it.

Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign implicitly ties self-meaning to the ability to do; and by doing, you have; and by having, you matter.

In 1994, Joel Drucker wrote in the LA Times, “The three-word message most closely associated with Nike is ‘Just Do It,’ a tagline not too subtly linking good old American pragmatism, sexual innuendo[,] and exemplary decisiveness. In an era when just doing anything is fraught with physical, emotional[,] and social complications, along comes Nike – they took the name of the Greek goddess of victory – with a call to action, turning what were once functional sneakers into cultural statements.”

Like a good existentialist, co-founder and then-CEO Phil Knight admits the advertising is more about “authenticity” than just a catchy phrase. Nike’s message was subtle, but it resonated: by doing, you will have; by having, you will be.

Why is this a problem (besides the LA Times’s outrageous omission of the Oxford Comma)?

The philosophy of existentialism – at least as it largely manifests itself in the 20th-century – starts with the assumption that the subject – the authentic self – is the supreme and authoritative existence. The subject pursues his or her passions not out of any objective – or external – morality, but solely by a morality that is internal.

God does not exist, says the existentialist; but if he did, that god must then first conform to my passions and standards to even be relevant. (To be clear, this is an articulation implied not only by the current agnostic, but by many current professing theists as well.)

Under this rubric, the “Just Do It” campaign can mean anything to anyone. The latest campaign illustrates this more clearly than any of its previous iterations do. “Believe in something,” it preaches, “even if it means sacrificing everything.” What is “something?” For that matter what is the “it” in “Just Do It?” Well, like the postmodern artists, Nike doesn’t want to define that for you, they’d rather invite you simply to respond.

The problem is – especially in a subjective, postmodern, existentialist world – two “somethings” (or two “its”) can be entirely contradictory in every respect, yet the implicit message commands us to affirm those “somethings” or “its” as valid, coherent, and true. It doesn’t take long for these “somethings” or “its” to reach the level of a crisis against our innate sense of objective morality. In 1997, for example, Marshall Applewhite “Just Did It” by encouraging 38 of his followers to evolve to their next spiritual level by committing suicide (perhaps rejecting Camus). Perhaps it was just coincidence they all wore Nike sneakers as their uniform of choice.

More to the present point, however, within the Kaepernick campaign, the division among supporters and opponents of Kaepernick’s actions is absolutely absurd. With this explicit philosophy Kaepernick supporters that oppose Trump must acknowledge that Trump is simply following the same exhortations that Kaepernick endorses. And Trump supporters that oppose Kaepernick must likewise acknowledge that much like Trump, Kaepernick is defying establishment totems to fulfil existential priorities.

That’s the problem, and the controversy and divisiveness surrounding Kaepernick and Trump is symptomatic. Nike is, and has been for three generations, encouraging their consumers to define goodness by what they do, what they have, and what they be; rather than insisting that our being – made in the image of God to love and worship Him first and to love our neighbor second – define what we should have and do.