In theory, Americans could control runaway healthcare costs if they shopped around for the best deal on big-ticket medical procedures. But in practice, there are limits to a patient’s willingness to compare doctors and hospitals when he’s clutching his chest while medical technicians slap an oxygen mask to his face and trundle him into an ambulance. Likewise, there may be limits if the treatment options are so complex and require such specialized knowledge that a layman cannot make an informed judgment.

Still, some procedures should lend themselves to comparison shopping. Take hip transplants, for instance. The procedure is easily explained by doctors, and the risks are readily grasped by patients. Rarely do patients require emergency surgery. They have ample time to check around to find the optimal balance of price and quality.

In 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control, surgeons performed more than 310,000 hip transplants. At an average cost of $40,000 per procedure, hip surgeries account for more than $12 billion a year in health care expenditures. Americans could literally save billions of dollars if they were empowered to spend as much time looking for the best deal on hip surgeries as they do, say, buying a car.

I had the opportunity last year to put that theory to the test. I had been suffering from an arthritic right hip for several years. While the discomfort usually was tolerable, the infirmity was limiting my mobility. I had trouble getting in and out of the car. I found it difficult to straighten my body when I stood up from a chair. I couldn’t walk more than a mile or so without my hip giving out. If I wanted to live an active life as I approached retirement age, I knew I had to do something.

My primary care physician referred me to an orthopedic surgeon in the Richmond area, Dr. Jason Hull. He took an x-ray of my hip and found that most of the cartilage had worn away — the hip and socket were scraping bone on bone. I was an obvious candidate for surgery.

Although he performed 450 to 500 hip and knee replacements a year, Hull confessed that he couldn’t tell me how much the procedure would cost — or even what he would charge. I’d have to ask the business office of his practice, Tuckahoe Orthopedics. As for what Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital would charge, I’d have to ask them.

While I liked Hull’s forthright demeanor and had full faith in his competence, I also felt a responsibility as a health care consumer to check out my options. Over and above what the surgery would cost me personally, I felt a moral obligation to see if I could save “society” some money. As it turned out, being a good health care consumer was all but impossible.

One idea particularly appealed to me. My friend Bill Moscowitz, a Virginia Commonwealth University pediatric surgeon, highly recommended Health City, a state-of-the-art hospital on Grand Cayman founded by renowned Indian heart surgeon Dr. Devi Prasad Shetty. Its value proposition: By focusing on a narrow range of high-volume procedures, it could provide treatment at comparable outcomes to the best U.S. hospitals but at much lower cost. Indeed, the hospital was known to put up the patient and a family member in a resort hotel on Grand Cayman’s famed Seven Mile Beach for post-operative recuperation. That sounded like a great way to recover from surgery! When the website confirmed that the hospital performed hip replacements, I had fantasies of my wife and me sipping margaritas and lounging under umbrellas on soft sandy beaches.

I submitted an email inquiry to Health City but, alas, the hospital never responded. Then I thought to inquire if my health insurance company, UnitedHealthcare, even covered procedures conducted at Health City. When I checked, the answer was no. That was a deal killer. It didn’t matter if Health City could under-price an American hospital by 50%, without insurance, I’d personally pay more. So, I restricted my search to hospitals in the Richmond area.

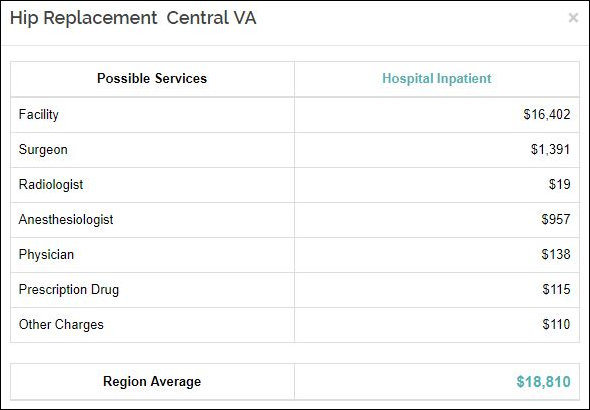

The Virginia Health Information website provides average cost data for various high-volume procedures performed in Virginia hospitals. Based on 2015 data, the website reveals that the average price of a hip replacement in Central Virginia — $18,810 — was lower than in any other region of the state. (The statewide average was $20,697.) As I recall, when I searched the website last year, it provided average cost figures for individual institutions. I can’t find that data any longer. Here’s all the database offers now:

Given the fact that a dozen Central Virginia hospitals conduct orthopedic surgeries, this table isn’t remotely helpful. As I recall, VFI data indicated last that Bon Secours St. Mary’s Hospital had the lowest, or almost the lowest, charges among the high-volume hospitals in the region. The hospital performs more than 2,000 procedures a year, and 10% of its total business consisted of orthopedic surgeries. Dr. Hull also conducted his surgeries there, so I felt certain that, whatever the price, at least I was assured of a positive outcome.

From a medical point of view, sticking with Hull and St. Mary’s turned out to be a good decision.

St. Mary’s had a pre-admission orientation program that provided useful information. Patients were instructed on what we needed to do before entering the hospital, such as showering with an antiseptic soap the week before surgery and applying a disinfectant hours before, in order to reduce the risk of infection. We also learned how to change clothing after surgery, and what exercises to perform to speed our rehabilitation. It was all very useful.

Then came the surgery itself. Everything went swimmingly. Only a couple of hours after post-op, I was hobbling down hospital corridors on a walker. By the next evening, I was ready to go home. I was astonished how such an invasive procedure — the surgeon cuts through the muscle, dislocates the femur from the hip socket, saws off the top, attaches a metal ball, and implants a metal socket before sewing you back up — would not cause more pain. Once I got home, I never needed the opiates they gave me, just some pumped-up versions of over-the-counter medication. The treatment included several in-home visits by physical therapists, which also was helpful. Within a week, I had tossed my walker, crutches and cane and was walking again. Hull was great, the St. Mary’s nurses were great, the therapists were great, and a half year later, my hip is great.

It wasn’t until a month after the surgery that I found out what it cost. Here’s the tally I received from United Healthcare:

Amount billed: $47,868

Plan discounts: $17,051

Paid by my plan: $26,754

Amount I owed: $4,063

Hull’s practice, Tuckahoe Orthopedics, charged $9,528. St. Mary’s charged $38,341.

That’s when it dawned on me that even if Tuckahoe and St. Mary’s had given me a list price, I still wouldn’t have had the information I needed to make an intelligent consumer choice. That’s because I didn’t know what discount UnitedHealthcare had negotiated with them — or with competing providers whom I might have consulted.

Even for a procedure as routine, high-volume, and standardized as hip replacement surgery, there is no price transparency in Virginia’s medical marketplace. Consumers have no leverage, and they exert no power. Physicians and hospitals charge whatever they charge for their own arcane reasons in interaction with equally inscrutable insurance companies.

If there’s one thing Americans can agree upon when it comes to health care, it’s that costs are out of control. The system is bankrupting the country. But no one agrees on the solution. Some say we should move toward a single-payer system which saves costs by stripping out the insurance middleman. I would prefer to move to a market-based system that saves costs through innovation. But you can’t have a market economy when consumers can’t discover prices.

Virginia’s efforts to promote price discovery through the VHI website are laudable but grossly inadequate. I don’t understand the health care industry well enough to opine on how to create price transparency. But I can say this: We know how to get to a single-payer health system but we don’t know yet how to get to a market-based health system. If conservatives and libertarians want to avoid government usurpation of the medical-insurance function, they’d better put on their thinking caps or the statists will win the debate by default.

James A. Bacon publishes Bacon’s Rebellion, a nonpartisan website focusing on public policy issues in Virginia.