Nike’s new ad campaign featuring NFL quarterback-turned social justice warrior Colin Kaepernick has everyone, whether they like it or not, pushing themselves to the brink of sanity by either screaming in streets in support, or taking their Nike socks, shoes, and sweaters off and burning them in disgust. In a meme-heavy world, copycat ads stylized in black-and-white have been created to exude an atmosphere of shame and comedy around Nike and Kaepernick in effort to show the world that everything the former quarterback has ever done is wrong, and Nike, one of the world’s largest apparel companies, should come crashing to the ground.

In such a politically-charged America, memes are understandable – this is the way we communicate with each other now. Forget words, well-thought-out sentences, eloquent prose, and civil discourse. Why do that when a picture is worth 1,000 words – especially when it can be hurled with barbaric sentiment.

Therefore, it seems that the adults of the world have unfortunately sunken to the depths of trolling teenagers, spouting off incoherent nothings, discourse unbecoming of a gentleman or a lady. Regardless, although parsimonious language is commonplace in today’s America, it seems that all responses – for and against – to the Kaepernick ad are plentiful, yet somehow not.

What is the true ontological nature of this ad? What would have made it better in the eyes of the naysayers? Would it have mattered in the end? Can I haz cheezburger? These are the questions that need to be posed.

Let’s begin with everyone’s favorite former NFL quarterback.

From 2012, the year after he entered the NFL, up until mid-2015, Kaepernick had a good career. Under the tutelage of Jim Harbaugh, Kaepernick and the San Francisco 49ers were a playoff contender, especially during the 2013 NFL season when the team went 12-4 in the regular season, only to lose to the Seattle Seahawks in the NFC Championship game.

In the middle of the 2015 NFL season, however, things took a sharp turn downhill. Kaepernick was demoted to backup quarterback as he struggled to find his rhythm under a new head coach (Harbaugh left to coach the University of Michigan), leading him to sit and steam about the loss of his stardom, a level of fame that had him appearing in ads across the sporting market.

In the third preseason game of the 2016 season, Kaepernick was noticed by sideline cameras to have been sitting down during the playing of “The Star-Spangled Banner” before the beginning of the football matchup between 49ers and the Green Bay Packers.

During a post-game interview, he explained his position stating, “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder,” according to a press release from the NFL, referencing a series of events that led to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Kaepernick added that he would continue to protest until he felt like “[the American flag] represents what it’s supposed to represent”.

One game later, Kaepernick opted to kneel during the national anthem, claiming his decision to switch was an attempt to show more respect to former and current U.S. military members.

Two years later, here we are.

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell has failed to implement a policy to enforce standing to respect the American flag during the playing of the national anthem, league ratings have continuously dropped, President Donald Trump said at a rally for then-Republican Senator Luther Strange, “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired. He’s fired!’” More importantly, the entirety (it seems) of the American populous is roiled in the battle: kneel v. stand.

So, why did Nike, a company that, to be honest, probably does not need a fierce advertising campaign, decide to do this?

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Nike’s “Just Do It” campaign. Nike’s fundamental objective has been to represent their brand as a fashion statement, which can sometimes be provocative – not insofar as what is being worn, but why it is being worn.

For those who have been living under a rock, or in North Korea, who have yet to be faced with the new ad, here it is, courtesy of Nike, an unaltered, black-and-white close-up of Kaepernick’s face with the slogan: “Believe in something even if it means sacrificing everything.”

Angry yet? Crooning over it already? Well, let’s keeping going with the story.

Angry yet? Crooning over it already? Well, let’s keeping going with the story.

“We believe Colin is one of the most inspirational athletes of this generation, who has leveraged the power of sport to help move the world forward,” Gino Fisanotti said, Nike’s vice president of brand for North America, according to a report from Forbes.

Yes, but what happened to Odell Beckham Jr., Serena Williams, Tiger Woods, and LeBron James? Aren’t they inspirational? Aren’t they trying to move the world forward with sport? They are, but that’s not what Nike is trying to appeal to.

It’s edginess – that’s the key here.

We’ve seen this before, though.

Think Kardashian.

Last April, Kendall Jenner, who is one of the Kardashians, apparently, starred in a Pepsi ad that featured a line of police officers getting ready to face off against a wave of protesters (presumably part of the BLM movement). However, Kendall came to the rescue, handing one law enforcement officer a can of fizzy, refreshing drink, leading to a bubbly, harmonious end to what would be considered as Ferguson 2.0.

Here’s the video:

Didn’t see it on television?

Well, that’s because Pepsi withdrew the ad, apologizing for putting Kendall “in this position,” as stated by a report from The Guardian.

So, why did no one like Kendall’s ad? Why, it was full of passion, social justice, and the colloquial “woke-ness” that some many youths cherish. The ad tells us to “Live Bolder,” because a can of tangy soft drink can pretty much end a riot.

*Disclaimer: please do not try that at home*

What happened in the Pepsi ad sets up the biggest question behind the new Nike ad campaign that no one is asking.

Obviously, Pepsi was capitalizing on the BLM movement, turning marching social justice warriors into benjamins. While people protested and lashed out against the unjustified killing of unarmed African-Americans, Pepsi was thinking, “how much money can we make off this?”

Regardless of what one thinks of Kaepernick, whether he’s a hero without a cape, or a zero in the political landscape, Nike is capitalizing on social justice, just like Pepsi did. That’s what should really irritate people. However, no one is talking about that.

People wish to burn their shoes because they dislike Kaepernick? Wouldn’t it be more justified to burn Nikes because the company is engaging in political profiteering?

Possibly, but the company, in all intents and purposes, can do whatever it wants – they’re not breaking any laws here.

Also, it’s interesting to note that no one is burning anything from the Jordan collection, or the Air Max collection, or VaporMaxs, or Yeezys, or any of the shoes that cost hundreds and hundreds of dollars. People are cutting up, burning, and throwing away pairs of Monarch IVs. So, the real victim here is Kohl’s.

Nevertheless, let’s digress.

So, what could have happened with a potential Nike ad campaign that wouldn’t have enraged so many people, all the while being edgy? Or, should they be edgy at all?

Edginess is the line balancing between acceptable and offensive, all while trying to impress, or get a point across. Edgy advertising is relatively easy. Instead of creating a 40-page thesis on why you should buy a pair of shoes, one can simply say, “You’re Terrible. Buy Our Shoes.” Thus, one ceases to be terrible when [insert brand here] is bought and one wears it.

Though, with the rise in edginess over the years, it has become mainstream. Once the market becomes inundated with edgy, offensive, voracious ads, people see them as commonplace. Look at the political climate. Look anywhere. Nowadays, America’s slogan is: “If You’re Not Offended, You’re Wrong.”

The entire point of edgy marketing is that companies, among other entities, are to say things that other companies and advertisers weren’t supposed to say. However, once every one is doing it, what’s the point? What’s edgy about the status quo?

So, what’s the antidote for this? The best ads are often the ones that connect in an honest fashion, in an open way to a potential client – not simply those that are vying for a cheap, emotional appeal to stimulate the senses. The best ads really make us think.

Today, September 11, 2018, marks 17 years since the terrorist attacks that consumed the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field near a coal strip mine in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. On that unfortunate Tuesday morning, 2,996 people were killed, and over 6,000 other were injured – not counting those that have died since due to health complications from the cleanup of the attacks.

A man by the name of Todd Beamer, 32, born in Flushing, Michigan, was aboard Flight 93 from Newark to San Francisco when four hijackers took control of the United Airlines’ Boeing 757, attempting to reroute it toward Washington, D.C., presumably towards the White House or the Capitol Building.

After a length of time, Beamer and a few fellow passengers had agreed on a plan to retake the plane.

Telephone operator Lisa Jefferson, who was connected with Beamer at that time would say later in an interview with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “I thought it was pretty dangerous. I asked him if he was sure he wanted to do that. He said at that point he thought that’s what he had to do.”

Beamer then set the phone down, with the line remaining open as Jefferson heard pandemonium in the background.

She heard Beamer saying, “God help me. Jesus help me.” Then, he addressed his fellow passengers before they stormed the cockpit. Still calm, he said, “Are you ready? OK,” Jefferson told of the tale.

Then, the words that would captivate millions: “Let’s roll!”

Those were reportedly Beamer’s last recorded words, shouted as he and his fellow brave passengers made the history-changing attempt to overpower the al-Qaeda operative Ziad Jarrah and his fellow terrorists, causing the plane to crash into the ground in rural Pennsylvania.

Deep below the White House, inside the Presidential Emergency Operations Center, Vice President Dick Cheney authorized Flight 93 to be shot down by U.S. fighter jets. However, upon learning the news of the crash, according to CNN, he is reported to have said, “I think an act of heroism just took place on that plane.”

We, as humans, like to memorialize acts of service, those the military brass would like to say are “above and beyond the call of duty.”

What is our call of duty? That, my friends, is the great ontological question.

For some, maybe Kaepernick has gone above and beyond the call of duty, like wearing socks during football practice emblazoned with pigs wearing police hats. For some, this could be the best the human race can really offer. That could be the best he has to offer to his movement. Or, possibly, more things are yet to come with him. Who knows?

However, maybe the belief still exists that there is something greater than making noise, greater than emotion, greater than something tangible.

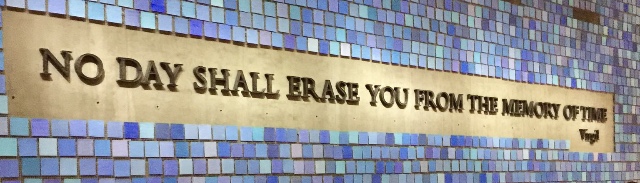

On the wall inside the 9/11 Memorial in Manhattan is a quote from Virgil’s “Aeneid”: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.”

For Beamer and the other few aboard Flight 93 that intervened, there is action without thought. There is service with no choice. There is an answer with no call. There is the memory that lives through the ages spurred by an ultimate sacrifice.

What did Beamer sacrifice?

He gave up his last few moments of life praying with his pregnant wife to save countless souls. There is no telling where that plane was heading, but it was heading to hurt people, somewhere. Beamer and his cohorts took it upon themselves to sacrifice their last few moments speaking with their loved ones to regain control of something that had been wrongfully taken.

That, my friends, is “Just Do[ing] It.”