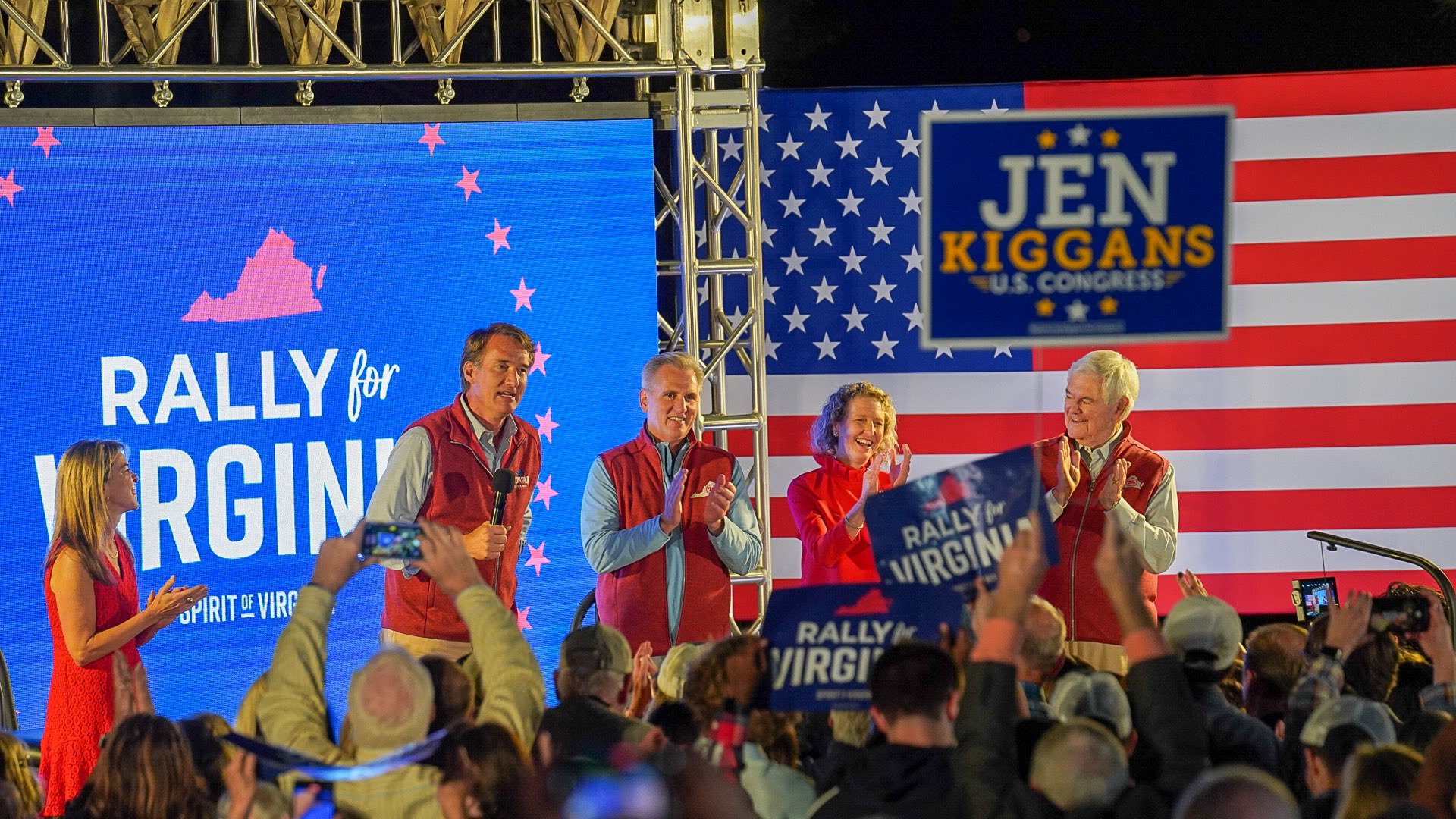

In his newly released energy plan, Governor Glenn Youngkin (R) makes it clear he sees the economic abyss created by the unrealistic and ideological green utopia demanded by his predecessor. Seeing a looming disaster and stopping it are two different things.

The new document is not a full 180-degree change from the previous plan concocted by former Governor Ralph Northam (D). For example, Youngkin is not reversing his previous endorsement of Dominion Energy Virginia’s planned $10 billion offshore wind project, a central part of the Northam plan. Also, Youngkin apparently is sufficiently convinced that carbon dioxide is harmful that he wants to spend your money on carbon capture and storage.

Nor does Youngkin call for outright repeal of the 2020 Virginia Clean Economy Act (VCEA), but rather he endorses removing its rigid mandates as to how rapidly to retire fossil fuel energy generation, and their mandatory replacement with wind, solar and related battery technology. The problem is even tweaks require amending state law, and previous efforts to do that were thwarted by the Democrats who still control the Virginia Senate and who still accept the Green New Deal catechism in full.

But the change in direction in the new document is dramatic, and it has already been roundly condemned by the various groups that are heavily advocating the rapid end of fossil fuels. By its enemies shall you know it. Placing concerns over customer cost and system reliability as a higher priority than reducing carbon emissions guarantees that the plan starts yet another ideological battle for the governor.

Under another recent law those advocates pushed through, the plan Youngkin issued October 3 was to be premised on a rapid move to a zero-carbon energy infrastructure, moving beyond transportation and electricity into agriculture and how to heat buildings and cook food. Youngkin didn’t just fail to comply with that directive, he rejected the premise.

From the news release that came out with the Energy plan’s announcement in Lynchburg:

The plan adopted in recent years by the previous administration goes too far in establishing rigid and inflexible rules for the transition in energy generation in Virginia. We need to recognize that a clean energy future does not have to come at the cost of a healthy, resilient, and growing economy. We first must embrace a measure of humility as to our ability to project and predict 30-years of energy demand and technological innovation. And we certainly should not make irreversible decisions today to exit critical elements of power stack.

The “measure of humility” includes statements that Virginia might not retire all or even most (or any?) of its natural gas generation by the current deadlines, will continue to push for additional natural gas pipelines to grow that energy source, and will not follow California into mandating only electric vehicles on new car lots by 2035. The report cites a Weldon Cooper Center estimate that the electric vehicle mandate will increase electricity demand by 25% (and that’s hardly the only electrification mandate from the Northam years) and then warns:

Transitioning from baseload generation (to wind and solar) while attempting to accommodate this increase in electricity demand could be a disastrous combination for Virginia’s grid reliability. California, which is now asking drivers to refrain from charging their electric vehicles to prevent blackouts, provides an instructive example of what banning non-electric vehicle sales and retiring all baseload generation would look like in Virginia.

Governors propose. Legislatures dispose. The votes to repeal the clean car regulations were not there in the 2022 General Assembly, at least not in the Senate. The attempt was made. It surely will be made again.

The absolute best elements of the plan, and here there is some bipartisan consensus, are centered on restoring the traditional and independent oversight authority of the State Corporation Commission. Several of Youngkin’s recommendations are complete reversals of recent General Assembly policies and practices which override the SCC, all adopted at the direct behest of the supposedly regulated entity. Passing them will not be easy, either, because in that case too many Republicans signed on to the earlier bills.

Some of the regulatory elements the governor is challenging go all the way back to the seminal 2007 legislation that established Virginia’s unique and consumer-dismissive electric regulatory regime. They include the proliferation of individual rate adjustment clauses on customer bills and the statutory profit margins protected by law.

A headline promise in Youngkin’s plan, probably unachievable within his term, is to develop a small modular nuclear reactor somewhere in Southwest Virginia. Appalachian Power Company serves that territory, and no regional electric cooperative would need or could ask ratepayers to fund such a project. A nuclear reactor is a bit more expensive than the usual highway or school construction project that gets tucked in a governor’s budget, and somebody needs to buy the power output.

Northam’s plan four years ago frankly laid out a deep green vision for an energy transformation, and he and his supporters then set about implementing it just about in full, aided by taking full control of both houses of the legislature for 2020 and 2021. It was far more a legislative wish list than an engineering and economic blueprint. Give them credit, they got it done.

The success of Youngkin’s plan will rise or fall on which elements of it are now translated into successful legislation. Even the 90 degree turn he proposes may require that various legislators face an electorate angry over 1) energy prices, 2) the threat to eliminate their preferred transportation or home energy choices and 3) the fear that the various investments in intermittent renewable energy will prove disastrous. (See Dominion’s refusal to actually back up its promises on offshore wind.)

Northam didn’t have the votes to do what he wanted in 2018 but did a year later. Youngkin now has a different (we say better) plan that also lacks sufficient support in the legislature, but another election is coming.