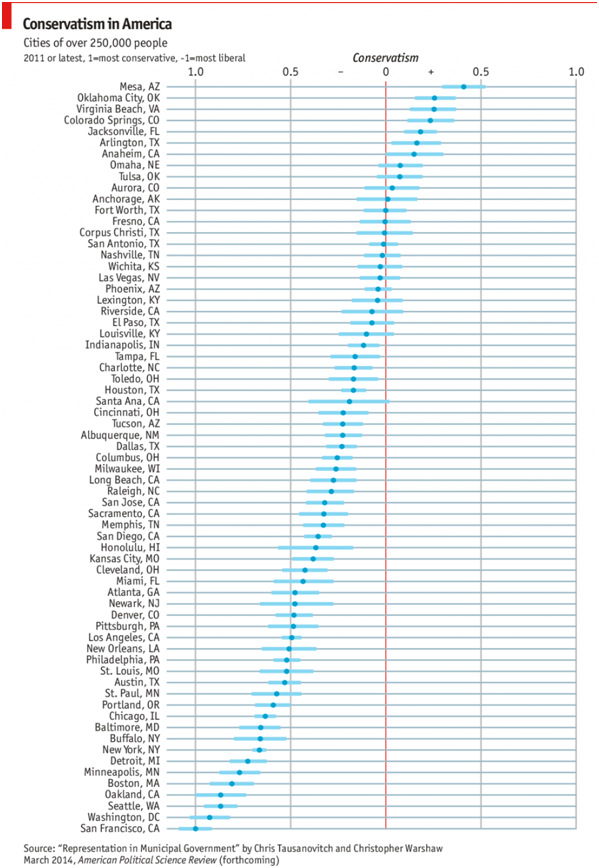

Alexandria (2016 pop. est. 155,810) is Virginia’s most liberal city. Among cities with populations greater than 250,000, Virginia Beach is the third most conservative in the nation, coming in behind Mesa, AZ, and Oklahoma City (see chart). The place where many Northern Virginians work – Washington, D.C. – is, according to the same MIT-UCLA study of large cities, the second most liberal large city in the nation, snuggled between first place San Francisco and third place Seattle. There are only 11 cities on the right-of-center side of the liberal-conservative divide, and the study found conservative cities to be a lot less rock-ribbed conservative than liberal cities are liberal.

This is hardly a surprise. Democrats are confident of winning the urban vote in any electoral contest. Republicans are confident in rural areas. In Virginia the two parties often don’t even run candidates in each others’ precincts, saving resources and energy for the suburban battleground. With Republican success in controlling state governments in other parts of the country, and Democrat dominance in most cities, the spotlight is turning to governance issues. In some parts of the country there is an increasing trend of Democrat-controlled city governments enacting local legislation to forward progressive agendas, and Republican-controlled state governments passing preemption bills “barring cities, towns and counties from enacting workplace wage, benefit and anti-discrimination laws.” Irony ensues. In an article “Red State, Blue City” in The Atlantic, David Graham points out:

In this context of increasing rural-urban division, people on both sides of the political aisle have warmed to positions typically associated with their adversaries. The GOP has long viewed itself as the party of decentralization, criticizing Democrats for trying to dictate to local communities from Capitol Hill, but now Republicans are the ones preempting local government. Meanwhile, after years of seeing Democratic reforms overturned by preemption, the party of big government finds itself championing decentralized power.

Urbanization in the United States did not end with the 20th century – the population continues to be increasingly concentrated in urban areas. It’s a straight-line extrapolation to identify the continued weakness of Republican electoral presence in urban areas that are continually increasing their economic and cultural dominance as a threat to conservative governance. As Evans and Hendrix point out in an article in The Federalist:

Eighty percent of Americans live in cities with over 150,000 people while generating roughly 85 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. … This electoral reality means that Republicans have little say over some of the most dynamic areas of the country. Cities are the engines of America’s economy and heart of its culture. Urban areas are thriving centers of productivity; a doubling of population density corresponds to a 10 percent increase in productivity. This productivity translates into opportunity, as San Francisco, which has both high productivity and high intergenerational mobility, demonstrates. Research indicates that every tech-industry job produces five more local jobs.

Big-picture political consequences of the urban-rural divide are much discussed. Topics such as what conservative governance would look like in day-to-day urban life are not. It increasingly feels as though Republicans have given up.

In the 1990s, Republican Rudy Giuliani succeeded in New York City by implementing policies based on the Broken Windows Theory, vigorously focused on preventing lesser crimes such as vandalism, turnstile jumping, and blackmail-by-squeegee which resulted in simultaneous reductions in serious criminal behavior. Success in New York City meant emulation in cities nationwide.

In the 1990s, Mr. Giuliani and 2-term Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan showed that, back then, electoral success was possible and governing with some degree of conservativism in overwhelmingly liberal cities could work. The Broken Windows Theory has been widely adopted by big city police departments throughout the country.

That success did not translate outside New York, as Giuliani was roundly rejected by national Republican voters. It’s telling that, to win in NY, Giuliani sought and received the endorsement of NY’s Liberal Party, and ran on a fusion Republican-Liberal ticket after NY’s Conservative Party declined to endorse him because of perceived deviations from conservative orthodoxy. Whether Giuliani was conservative enough was an issue in his national campaigns. Republican primary voters concluded that he wasn’t.

We don’t have to look far to find examples of what the absence of competitive Republicans and therefore of conservative governance in urban areas has wrought. Detroit is example number one, but, as the Washington Post explained, “Detroit does not vote for Republicans.”

The same could be said for 60 to 70% of voters in NoVa. We must continue to look for ways to bridge the divide between urban and non-urban voters to avoid fulfilling Jennifer Rubin’s prediction that Bob McDonnell was the last Republican governor of Virginia.