As Richmond-based Dominion Energy begins moving into and expanding its current alternative energy sources – wind power, hydroelectric, solar, nuclear fusion – their move away from traditional coal sources has lead them to make some quite interesting investments in the quest to traverse beyond fossil fuels. For example, the utility company is now teaming with Smithfield Foods in a $250 million joint venture to convert biosolids into viable energy.

When we say biosolids, we mean hog manure, and lots of it.

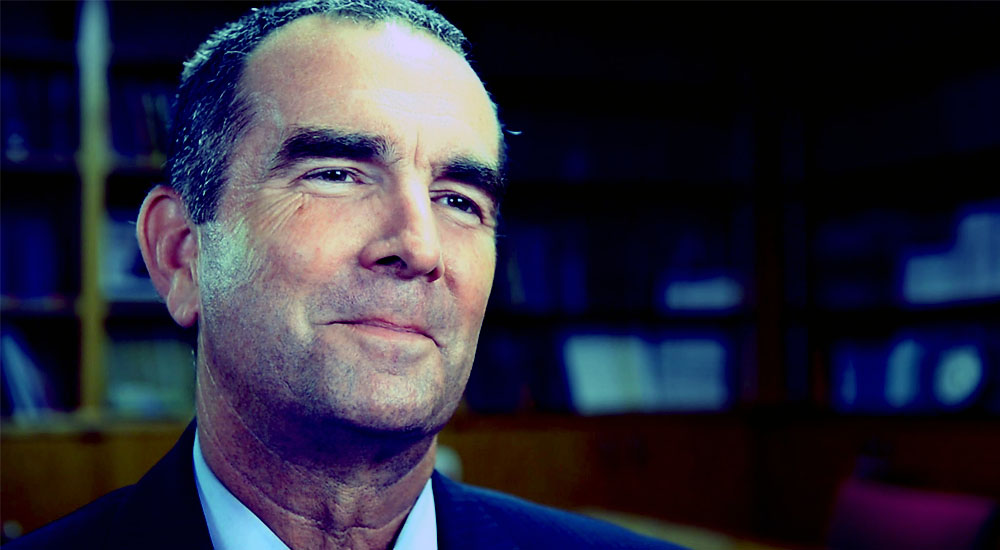

“With this transformational partnership, we are combining the environmental benefits of renewables with the reliability of natural gas to meet the around-the-clock clean energy needs of consumers and businesses,” Dominion CEO Tom Farrell said in a statement in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

As the Commonwealth’s largest electric utility conglomerate, Dominion claims they have already reduced their carbon pollution by more than 40 percent in the last 10 years. The company forecasts that the “hog farm” renewable natural gas project will prevent “10 billion cubic feet of methane from entering the atmosphere, the equivalent of removing 120,000 vehicles from the road.”

Dubbed “Align Renewable Natural Gas,” the four-stage project will include one installation in the Waverly area of Sussex County, with others located at an array of farms in North Carolina and Utah – two states where Dominion operates a natural gas transmission system, as well.

Smithfield Foods-affiliated farms would have their volume of hog manure capped, with a contract negotiated with Dominion for a long-term supply. Afterwards, a process occurs that converts the biosolids into methane gas, accompanied by a small amount of carbon dioxide.

According to a study from the University of Missouri:

“Livestock manure contains a portion of volatile (organic) solids, which are fats, carbohydrates, proteins and other nutrients that are available as food and energy for the growth and reproduction of anaerobic bacteria.

The anaerobic digestion process occurs in two stages. The volatile solids in manure are initially broken down to a series of fatty acids. This step is called the acid-forming stage and is carried out by a particular group of bacteria, called acid formers. In the second stage, a highly specialized group of bacteria, called methane formers, convert the acids to methane gas and carbon dioxide.”

When the processing plant has completed converting the biosolids into usable, renewable energy, Dominion plans to deliver the “natural gas” to local distribution systems in Waverly, Virginia.

WRIC reports that Columbia Gas of Virginia and Virginia Natural Gas have signed on to use the renewable resource. For now, the application is set for residential and business use, but in the near future Dominion plans to expand to have their methane gas used by power plants to generate electricity for a large portion of customers.

Farrell added that as methane production increases in the future, it would be transported via the currently under construction, 600-mile, $7 billion Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) due to its close proximity to the North Carolina hog farms. In its work to curb greenhouse gases, Dominion says the renewable natural gas venture will reduce emissions of a primary source of greenhouse gases linked to climate change.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) says that methane, the simplest hydrocarbon, is “pound for pound…25 times greater than CO2 [carbon dioxide] over a 100-year period,” for its comparative impact on the atmosphere. Dominion’s CEO said the converted natural gas is “carbon negative,” meaning that it would produce far less methane than the carbon dioxide that would be released when burned by gas customers.

Methane emissions have trended downwards for almost three decades, mainly coming from agricultural sources like hog farms. Considering hog waste lagoons also pose a potential environmental threat from hurricanes and other sources of flooding, letting their contents leak into groundwater aquifers, harnessing the energy from the gases and getting rid of the large quantities of manure is, as Smithfield CEO Kenneth Sullivan said, “a true win-win.”

Ultimately, Dominion estimates that the renewable source could displace up to four percent of the natural gas it extracts via hydraulic fracturing, more commonly known as “fracking.”