On August 16, 1852, an article defending future president Franklin Pierce against charges of anti-Catholic sentiment ran in the Lynchburg Daily Virginian.

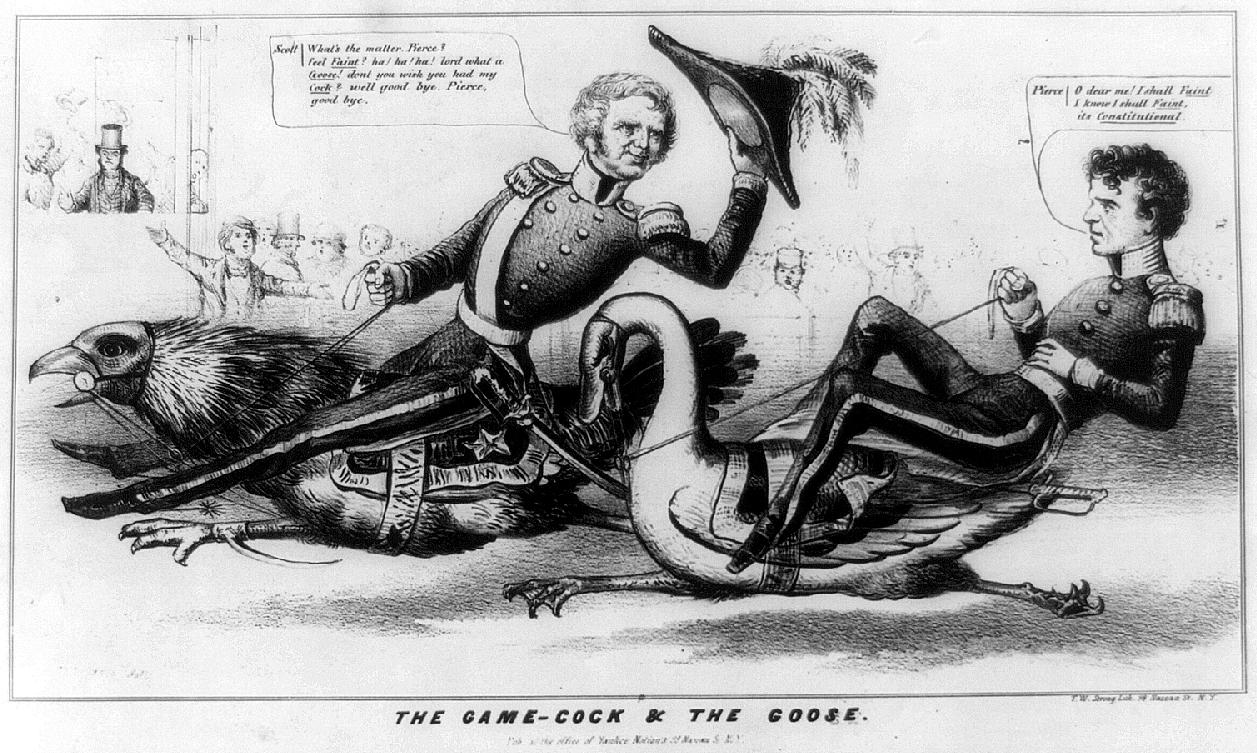

While the election of 1852 was for the most part unremarkable – Democrat Pierce won in a landslide over Whig Winfield Scott – there were at times some charges against Pierce that attempted to bring him down. One of the most often-repeated claims was that General Pierce was in favor of discriminating against Roman Catholics.

The newspaper explains:

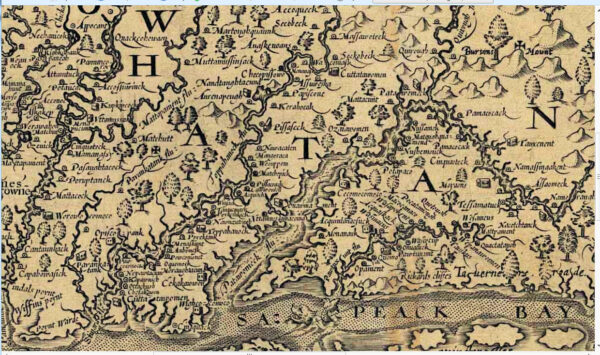

“Mr. W.E. Robinson, an active and enterprising Irishman in New York…has been down to Concord, New Hampshire, to examine the course, which General Pierce pursued on the clause in the [New Hampshire] Constitution, disqualifying Catholics from holding office.

“It will be recollected, that the day after Pierce was nominated, Mr. [George] Dallas made a speech in Philadelphia and vindicated Gen. P., from the charge…that he was in favour of the bigoted clause in New Hampshire Constitution [sic]….”

Winfield Scott had commanded Franklin Pierce in the Mexican-American war, and had used his campaign to portray his former subordinate as weak and fatigued. And as Jean Baker, professor of History at Goucher College explains, “The campaign of 1852 was the first to acknowledge the foreign born as a political force.”

Interestingly, though there was a loud and active anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments, both parties fled association with that camp. Winfield Scott bragged that his daughter attended school in a Catholic convent, and tried to sway immigrants to vote for him by painting Pierce as the opponent of the papacy. Pierce’s allies vehemently defended against the charges.

In the Lynchburg article, it mentions that Mr. Robinson went to great lengths to discover that, contrary to his opponent’s charges, Pierce was the victim of a coordinated deception to make it appear in the New Hampshire legislative journals that he had given a speech against “Catholic emancipation”.

The Daily Virginian noted, “We have no recollection of a baser or more contemptible fraud than this.”

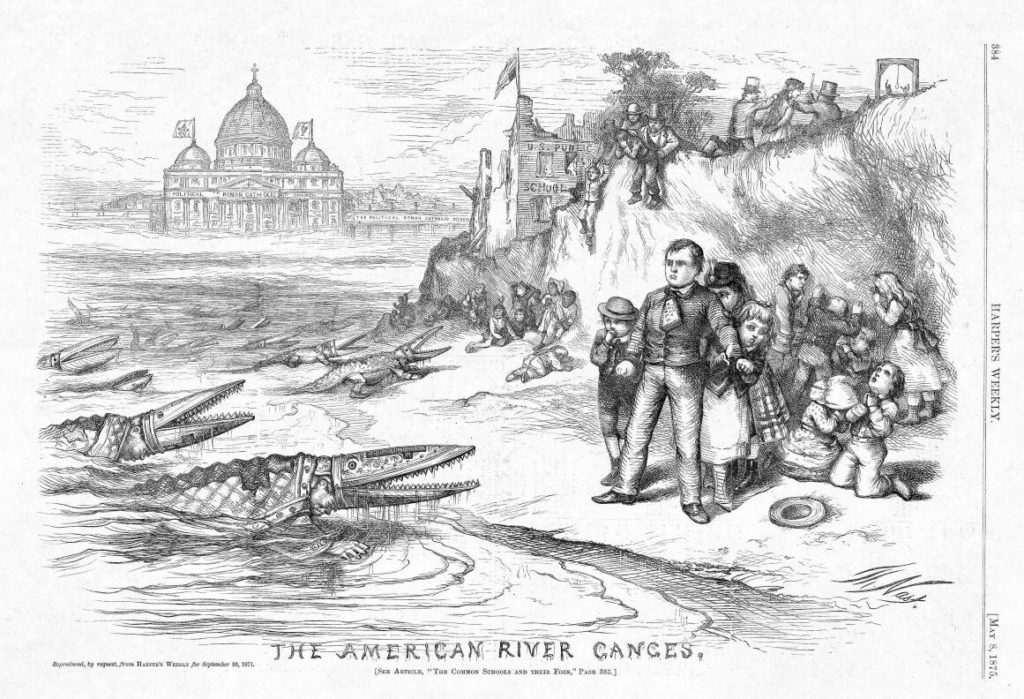

While these two candidates refused to participate in the nativist narrative against immigrants and Catholics, the identitarian influence and volume was just enough to spawn the creation of a Nativist party called the “Know Nothings”. This explicitly anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic movement succeeded in recruiting former President Millard Fillmore – who succeeded Zachary Taylor as president after Taylor died in office, and did not receive the Whig nomination in 1852 — as their standard bearer in the 1856 presidential election.

Though Fillmore sought later to disassociate himself with the nativists, the fact remains that he consented to run on their platform.

Now we come 165 years later to an era of nativism and anti-immigrant populism. The nativists in 1852 believed Roman Catholic immigrants would be unable to assimilate to American culture; the nativists in 2017 believe likewise – just about a different group of immigrants. The nativists in 1852 were loud with some influence – but many more others in 1852 America refused to be the nativists’ marionettes, and history remembers the anti-Catholic nationalists only in a negative light.

Catholics continued to suffer discrimination at the hands of nativists, but they did assimilate into the United States, and now they are legislators, governors, and occupy a majority of the Supreme Court of the United States. They are the staunchest defenders of the life of the unborn; and their intellectual contributions to the United States in science and the arts is immeasurable.

Though I am not Roman Catholic, I for one am glad that our former presidents refused to make themselves beholden to a small but vociferous group of nationalists intent on expurgating people not like them.