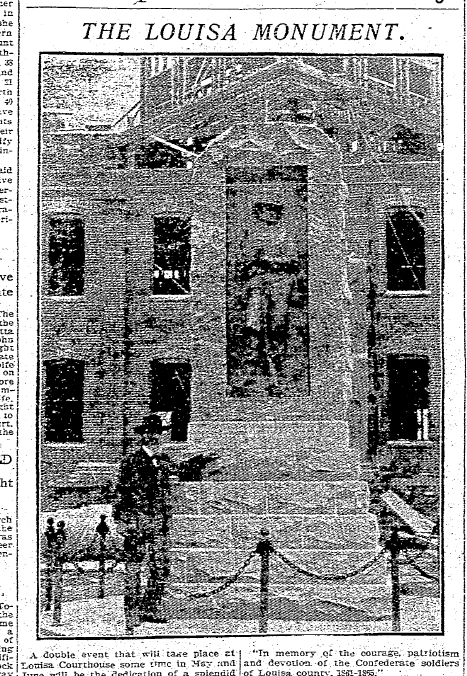

On August 17, 1905, Louisa County held a ceremonious event unveiling its new “monument to the Confederate soldiers of the county, living and dead.”

Planning for this monument began at least two years earlier, when a group of county thespians called the Louisa Amateurs performed F.A. Scudamore’s “Because I Love You” “to raise funds for the erection of a monument to Louisa’s Confederate dead.”

Momentum for the erection of the monument increased, and as August 17th drew nearer, anticipation grew throughout Central Virginia, and even beyond. The Richmond Times Dispatch ran an article on March 22, 1905 – complete with a picture of the monument – and forecast “The occasion of the unveiling will draw together nearly the entire population of [Louisa] and will be made a red letter day in the history of Louisa.”

A special train was set to run from the Main Street Station in Richmond to Louisa, for those in the capital who wished to attend, and fare discounts were given to Confederate veterans by the Chesapeake & Ohio railroad.

The monument received accolades from around the country – including the North. Elmer Burruss, an artist from Philadelphia, called the monument “in every way deserving of unique distinction among monuments of its class, not only in the South, but throughout the whole country. Especially should they be congratulated in this at a time when there is so much that is bad and meaningless in sculpture.”

Burruss remarked not only on the content, but on the atmosphere surrounding its meaning. “Above all things the Confederate soldier was an individual…who could not become the indefinite portion of a mass, but, like Harry of the Wynd, fought for his own hand. He was a self-sacrificing hero, who claimed no distinction, and desired only that he should be in the line of duty to himself, his country, and his God. We owe it to him to keep his memory green. Dying, his head pillowed on the bosom of his mother, Virginia, we owe it to ourselves that his name should be honored.”

The Richmond Times Dispatch reported, “Never in the history of Louisa county, in the memory of living generation, has such a crowd been entertained at the county seat as that which was present here to-day.” The newspaper estimated between 4,000 and 5,000 people attended (at a time when Louisa County boasted only 16,000 residents).

At least 70 Veterans of the Civil War were in attendance, including Brigadier General William McComb, “a gallant son of Louisa,” who was injured at Chancellorsville, “which has left its marks to this day.”

The keynote speaker, Rev. Dr. J. William Jones, Louisa native and Civil War chaplain, remarked:

“A great Virginia orator once said: ‘When Pickett’s Division made its immortal charge at Gettysburg, the Muse of History stood with uplifted pen to write the birth of a new nation, but their supports failed. They were overwhelmed, surrounded, and their remnant forced back. The muse of history then turned aside, and with a pen of iron and ink of blood wrote the failure of a brave people struggling for Constitutional freedom.’

“It is within my personal knowledge that our great leader, Robert Edward Lee, died believing that if his orders had been obeyed at Gettysburg he would have won that battle, and ‘that a decided victory there would have been given us Washington and Baltimore, if not Philadelphia, and have established the independence of the Confederacy.”

Jones continued to tell personal stories of individual soldiers with whom he served from Louisa, some humorous, some heroic. He told the story of “Tap” Trice, who willingly traded prison guard duty for front-line fighting, where he was wounded five times – “refusing to leave the field until the last wound rendered him unconscious…Nearly blind, he survives still, and I greet my old comrade here to-day as ‘the bravest of the brave.’” He also told the story of two brothers from Louisa who were killed on that same day.

The monument was presented to the Commonwealth’s Attorney General in Louisa by the Confederate Veterans and the Ladies’ Monument Association, among whom many had lost husbands, brothers, and fathers in the War.

The Time Dispatch concludes the article by describing the interaction among the guests: “Besides the reunion of the veteran soldiers, there were many smaller reunions of families and of kinsmen long separated – for hundreds of Louisa people had taken advantage of this opportunity to meet the comrades and friends of their boyhood, youth and manhood or womanhood. It seemed to a stranger that the majority were related to each other in some way.”

In the current debate over monuments, the simple summary is that one side is committed to preserving history while another is committed to removing what they see as hateful blemishes of the past.

But in reality, the arguments are much more complex, and much more personal – for both sides. There are very emotional attachments or repulsions to the statue. It is easy, I suppose, more than a century removed to ascribe malicious and racist motives to the sculptors, and to assume the priority of their social issues were the same as ours now. It’s easy to simply dismiss a Confederate statue as a memorial to the worst in us all when the sculptor and all who commissioned it are long-since dead. And then it’s easier to disgrace a memorial to sin than it is a memorial to family.

But it’s harder to try to understand an historical worldview – a mindset, or system of thought. For those in Louisa, at least in what is recorded, there was no longing to return to a system of chattel slavery when they began raising money for the monument. Instead, throughout the records, it seems family members were mourning and memorializing the loss of family members; that these family members seemed to have died in vain in their struggle for independence; and that perhaps – just perhaps – their camaraderie, service, and death in battle could mean something if a permanent reminder were erected.

It’s dangerous and wrong to ignore the iniquities of our heroes; but it’s also dangerous and wrong to prescind or ignore the virtues of our adversaries.

I sympathize with those who want to tear down the monuments – I do. Emotions are powerful things, and symbols or things that are perceived to attack self-worth and self-dignity are critically important. Symbols or things that seem to prioritize a social philosophy repugnant to your own means the future of society is at stake.

But it could be – it could just be – that these monuments are very much like tombstones to those who wish to preserve them; there’s a familial attachment, not an economic or social one. And just as many people find reminders of their self-worth in tombstones as those who are threatened by them.