The inestimable Jim Bacon writes about how the UVA Alumni Association’s magazine Virginia has declined to run an ad from the Jefferson Council regarding the Jefferson-Hemings controversy, deeming the ad a violation of its policies.

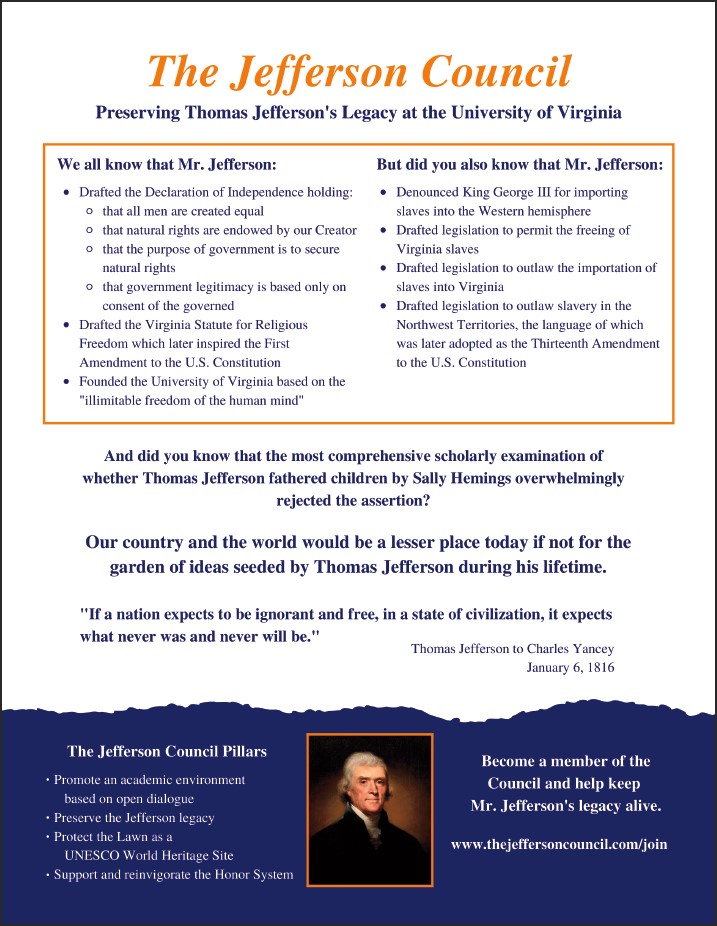

Above is an ad that The Jefferson Council submitted to run in the University of Virginia Alumni Society, Virginia. Before I tell you the fate that befell this ad, please take a moment to read it, and then ask yourself: Is there anything political about it? Is there anything contentious about it? Is there anything inaccurate about it?

Sure, you might disagree with the thrust of the ad. Maybe you think, like many people at UVa do, that Jefferson deserves to be remembered in history as a slave-holding rapist. But, really, do you find anything objectionable about the facts, the quotes or the tenor of the presentation?

Apparently the editor of Virginia Magazine did find the advertisement questionable. In response, recently appointed UVA Board of Visitors member Bert Ellis asked the president of the UVA Alumni Association for a response, which ran as follows:

Congratulations on your appointment to the BOV.

Richard consulted me before responding to Tom. As he said, you can edit this ad or we can run the previous version. Let us know what you decide.

Now I’d be curious to see what the previous ad said. The tactic is a tried and true one, especially for organizations deemed beyond the pale. Submit an anodyne ad, have it approved, submit a revision, have it declined, etc.

Yet the wider complaint echoed by Bacon and others is important to consider in all of this, namely that the present-day narrative regarding the patrimony of Sally Hemings’ children is and remains highly controversial and by no means settled, with the wider problem that the University of Virginia itself is seeking ways of reducing Mr. Jefferson’s presence and role at Mr. Jefferson’s University:

Many alumni would be shocked to know the low esteem with which the university’s founder is held today. Jefferson is commonly referred to as a slave-holding rapist, as if (a) the rapist charge were beyond dispute, and (b) those were the only attributes about him worth remembering. This commonly accepted belief, now widespread in the popular culture, has seeped so deeply into the student body that student guides showing visitors around the grounds sometimes refer to him this way.

In 2000 Jefferson Council member Bob Turner, a UVa law school professor, headed the Turner Commission of more than a dozen senior scholars to examine the historical and literary evidence that Jefferson fathered one or more of Hemings’ children. In the most thorough investigation of the matter ever conducted, panelist conclusions ranged from “serious skepticism” to “almost certainly false.” The report has been largely ignored ever since by ideologues intoxicated with the idea of knocking down a U.S. icon a few pegs.

Common sense might declare that the controversy over Sally Hemings is no more controversial today than it was in the 1990s when it was reignited from the psychoanalytical work of Fawn Brodie in the 1970s by Annette Gordon-Reed. William Hyland’s 2009 rebuttal of Gordon-Reed’s work has since been followed up by Holowchak’s 2013 work, neither of which have been grappled with in any meaningful or serious form by the establishment view.

Consequently, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has done an extensive rework of the Monticello estate, not only recontextualizing the grounds to reflect the realities of plantation life but going so far as to removing the men’s bathroom — peculiarly placed — that had been located inside Sally Heming’s rooms underneath the South Pavilion while reinterpreting much of Mulberry Row and the gardens to reflect the work of Jefferson’s slaves (or the euphemism “enslaved persons” which one suspects does more to sooth the consciences of so-called liberal allies than it does to reflect the cruel realities of human enslavement).

Dumas Malone’s extensive work shows that Thomas Jefferson was present at Monticello at every opportunity that Sally Hemings might have conceived children. The DNA testing performed in the 1990s has proven a source of controversy, as any male descendant of the Jefferson line could be the father — Peter Jefferson and Randolph Jefferson being the two most likely culprits.

For myself, Sally Hemings’ life perhaps stands as the single greatest testament as to the veracity of the claims. When Jefferson died and Monticello eventually sold, Hemings was effectively ostracized by the free black community in Charlottesville. Reduced to seamstress work, Hemings was most likely buried at what is today the parking lot of a Charlottesville hotel. Not a part of history most prefer to discuss… but Hemings remaining years and death point towards her condition as something more than just a house servant among many other house servants.

If you haven’t read Annette Gordon-Reed’s 1998 book, one should do so. It reads as a legal brief, which can be tiresome for historians, yet one understands why Gordon-Reed did so (not just because she is an attorney by profession, but because the case had to be laid out as such). Hyland’s rebuttal is more fire than brimstone, but worth reading as well.

Yet the wider objection that the Jefferson Council raises — namely that proponents of the Jefferson-Hemings relationship are cramming facts into a hypothesis — remain a credible criticism.

Too many have noted the transition by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation of “Sally Hemings’ Monticello” as perhaps missing the mark. After all, enslavement was a ubiquitous feature on many a Virginia plantation.

Monticello stands out not because of banality of the peculiar institution, but rather because Jefferson — unlike his peers — wondered aloud about what a free nation might look like. Is he to be condemned as a hypocrite? Or is he to be celebrated as someone whose vision was almost too excellent for even Mr. Jefferson’s character? Isn’t that contradiction as deeply inherent in us as the very same rights Jefferson explicated in our Declaration of Independence? That the pursuit of these rights and not solely their achievement is the duty of any free society worthy of the name?

For historians, much as there is no such thing as unquestionable science, there should be no such thing as unquestionable history. Reproducibility and replication based on record and evidence remains the gold standard.

If the question is being raised in good faith (and surely the Jefferson Council is raising the question in good faith) then surely it should be answered in good faith.

More to the point — and the Jefferson-Hemings controversy is perhaps a stand-in for this wider conversation — is how the memory of Mr. Jefferson should be preserved at the University. Again, Bacon observes:

Not only is the [Jefferson-Hemings] case settled, but apparently the findings of Jefferson’s paternity are no longer to be questioned. The new orthodoxy must be enforced.

In one of his most oft-quoted statements, Jefferson wrote in a letter to Lewis Shepherd in 1820, “This institution [the University of Virginia] will be based upon the illimitable freedom of the human mind. For here we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.”

Ah, yes, follow truth wherever it may lead… unless that supposed truth portrays the author of that statement as a slave-holding rapist.

UVA is not alone in this tidal wave, despite calls to remove Mr. Jefferson’s statue from outside the Rotunda and now-successful attempts to turn the UVA Honor Committee into yet another rubber stamp for bad behavior — transitioning what was once a defining characteristic of the University into a merely heightened awareness of an act of lying, cheating, or stealing.

Certainly Washington & Lee remains in its chrysalis phase in its Kafka-esque metamorphises into Ampersand University. The College of William and Mary continues to convulse alongside Colonial Williamsburg. The Virginia Military Institute — stripped of General Jackson’s presence among other so-called reforms — remains the victim of one overzealous reporter whose quill pen excuses every attempt to reforge the institution into something meaningless. Not a single public college or university seems to have refused to bend the knee to the postmodern inquisitors.

Of course, Virginia carries traditions that are not only deeply felt but more ubiquitous in its presence, ergo there is more work than the iconoclasts can handle. One wonders whether the Wren Cross at William and Mary would stand any chance today versus the student-led revolt against its removal in the 1990s. Yet the very fact that the true aim of these so-called progressives is to “humanize” and “contextualize” our Founding Fathers to such a degree as to render then unexceptional should alarm many a historian and most Virginians as cynical at best and agenda-driven at its very worst.

There is a reason why we celebrate these leaders, and it is because unlike their peers they were indeed exceptional men. Jefferson could have been irresolute; Washington could have enjoyed his foxhounds; Mason and Henry could have remained lawyers; Marshall could have remained a judge. That they did not should warrant some merit, even if they do not measure up to the enlightened (sic) abstractions of the post-progressive 21st century political left.

“The great enemy of progressive ideals,” reminds Saul Bellow, “is not the Establishment but the limitless dullness of those who take them up.” One might helpfully suggest that — if we are to prove ourselves as exceptional as Mr. Jefferson — we limit our dullness and expose our ideas to the light of open debate.

Virginia Magazine should consider an alternative view, free from prejudice but not from judgment, and let the facts demonstrate themselves free from narration. After all, this was the justice Sally Hemings and her children were denied for so very long.

Shall we repeat that mistake in her defense?

NOTE: The author is a dues-paying member of the Jefferson Council and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, does not (sadly) donate to the UVA Alumni Foundation because he was never really asked, really loves visiting Monticello, enjoys fried chicken at Michie Tavern, is super happy with the South Pavilion restoration work, is gratified to be a UVA graduate, and most importantly would very much like to cheerfully participate in and visit all of these institutions without being thought evil, hostile, too conservative, a troglodyte, or an otherwise bad person. I am both conflicted in interest and interested in conflict — and more importantly, hope for a happy mediation.

2 Comments

[…] with permission. See the original article here and leave some […]

[…] with permission. See the original article here and leave some […]

Comments are closed.